The Aftermarket Right That Shouldn’t Be An Afterthought

The Aftermarket Right That Shouldn’t Be An Afterthought

The right to repair is a handy weapon in the protective legal arsenal of the cartridge remanufacturer and printer service technician. It’s so well-established, it’s easy to forget it exists. But it shouldn’t be forgotten, nor taken for granted.

The right to repair is a handy weapon in the protective legal arsenal of the cartridge remanufacturer and printer service technician. It’s so well-established, it’s easy to forget it exists. But it shouldn’t be forgotten, nor taken for granted.

In April, its power was once again evident, when a handful of small service companies took on international giant General Electric Company (“GE”) in a case that claimed GE engaged in anticompetitive conduct in the servicing and repair of anesthesia machines.

GE is one of the largest manufacturers of anesthesia gas machines in the United States.

The plaintiffs, small companies that offer low-cost repair services for GE machines, alleged that GE tried to shut them out of the repair business through anticompetitive conduct.

First, they claimed that GE ceased selling parts for anesthesia machines at list prices in 2011, and appointed a sole supplier of parts, which hurt competition, by raising costs to the plaintiffs and delaying their response and repair time.

Another allegation against GE was that it created a policy that made it impossible for the plaintiffs to get their service technicians trained on new models of GE machines. This restriction on training would have forced all of the plaintiffs out of business within five years, conduct the plaintiffs alleged to be in violation of the antitrust laws. The Texas jury agreed.

In the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, the jury awarded actual damages of US$ 43,803,344. Under federal law, the damages are automatically tripled to US$131.4 million.

“The verdict was a call for fairness in business, and it was a real victory for the little guys that were brave enough to take on a major corporation,” said Sam Baxter of McKool Smith, lead counsel for the plaintiffs. “We are delighted with the jury’s verdict.” This case follows 1992’s “Kodak” Supreme Court case, which determined that Kodak was illegally monopolizing access to service parts on its copiers. (Eastman Kodak Co. v. Image Technical Services, Inc.)

The right to repair – a tale of two rights

The right to repair has legal import in two ways. First, there is the right to repair as outlined in the GE case. Although

GE has a right to protect its patented technology in its anesthesia machines, it may not exclude everyone from repairing them. Manufacturing an item does not give the OEMs an absolute right to service it or provide parts for it during the rest of the machine’s life.

That right passes to its owner, who paid for the machine and, in doing so, extinguished all its patent and other intellectual property rights. Likewise, the right to repair also extends to subsequent uses of the product. If

the owner wants to turn the machine into an air freshener dispenser, he may. The only thing prohibited is

the making of a brand-new machine, as that would violate the patents held by the OEM. The new machine would infringe the patents held by the OEMs.

THIS DISTINCTION PROTECTS THE PATENT OWNER AGAINST ONLY THOSE WHO RE-MAKE THE INVENTION ANEW, WHILE PROMOTING THE PARAMOUNT PUBLIC INTEREST IN COMMERCE PERTAINING TO PATENTED GOODS.

Equipment remanufacturers have enjoyed the umbrella provided by this right to repair against the deluge of patent infringement cases brought by OEMs for centuries now. The doctrine of non-infringing repair is nearly as old as the American industrial revolution. Since the start of the U.S. industrial revolution in the 1800s, permissible repair has

been found to be legal across commerce, in products including automobiles, surfboards, medical devices, injection molding machines, cooking devices, disposable cameras, computer printers, and—of course—printer cartridges.

A good example of the right to repair an item was discussed in Aro Manufacturing Co. v. Convertible Top Replacement Co. The specific controversy in the Aro case concerned the replacement of a fabric top portion of an automobile convertible roof assembly. Fabric convertible tops often wore out before the cars and top frames to which they were attached. Natural wear and tear took their toll. Car owners wished to replace the cloth part without buying an entire new convertible top assembly. A patent covered the combination of the cloth and many metal parts that remained serviceable. Aro was a company that engaged in the supply of replacement cloth tops that fit various car models. Because Aro declined to pay a royalty to the patentee, patent infringement litigation followed.

In the Aro decision, the U.S. Supreme Court distinguished permissible repair from the infringing reconstruction. “Mere replacement of broken or worn-out parts, whether of the same part repeatedly or of different parts successively, is no more than the lawful right of the owner to repair his property”; and such replacement constitutes lawful repair regardless of how “essential each non-patented part may be to the patented combination and no matter how costly or difficult replacement may be.”

This distinction protects the patent owner against only those who re-make the invention anew while promoting the paramount public interest in commerce pertaining to patented goods. Automotive parts businesses commonly repair hundreds of reusable parts (e.g., transmissions, alternators, brakes, clutches, and controlled velocity joints), and repair shops customize and upgrade car engines using aftermarket parts.

This right to repair has been extended to printer cartridges in cases like Repeat-O-Type Stencil v. Hewlett-Packard Co. Suppliers in the imaging industry repair toner and inkjet cartridges for business and home office use with specialized mechanical parts and computer chips that regulate and upgrade printing operations. Consumers upgrade computers by adding storage, memory, and graphics processing and gaming boards. Consumers benefit from this competition through lower prices, higher quality, and competitive features.

In 2000, Lexmark International tried to use the Digital Millennium Copyright Act to scale back the right to repair. It followed other OEMs that claimed repair and replacement of their software-encoded chips violated the copyright provisions of that law. Companies that repaired products controlled by functional software, such as printers and printer cartridges, garage door openers, and auto parts, had to re-establish their right of repair under the new law and were successful.

Static Control Components was the first in the imaging industry to face litigation under the DMCA, and successfully defended against one of the most notorious attempts to use it against aftermarket competition. In 2003, Static Control successfully argued that the DMCA should not apply to the circumvention of a technological measure intended to lock- out competition for remanufactured printer cartridges. Thanks to that litigation, the law now provides that the DMCA should not cover these types of circumventions.

The right to repair versus new “reconstructed” cartridges

OEMs patent every function and little nuance of every cartridge. I once marvelled over the way one OEM had patented even the thumb guides for the placement of cartridges into the printer. Printer OEMs file record numbers of patents every year. One cartridge’s design and function may incorporate thousands of patents.

JUST BECAUSE AN AFTERMARKET COMPANY CLAIMS TO HOLD A PATENT, DOES NOT NECESSARILY MEAN THAT PRODUCT CEASES TO INFRINGE THE PATENTS OF THE OEM.

Over the past two decades, a remanufactured cartridge has been adjudicated as a permissibly-repaired cartridge. A new mold cartridge is not a permissibly-repaired cartridge. It is a newly-reconstructed cartridge. It may violate one or more of those OEM patents, no matter how loudly their manufacturers proclaim them to be “patent-free,” “infringement- free,” or other marketing reassurance. Just because an aftermarket company claims to hold a patent, does not necessarily mean that product ceases to infringe the patents of the OEM. Only a court can make the final determination should an OEM wish to test it.

The right to repair is the better defence and protection against the OEMs’ patents. A new cartridge is not a repaired one and therefore is an invitation for a patent infringement lawsuit.

What to do to make best use of the Right to Repair?

Savvy imaging supplies business dealers:

- sell remanufactured cartridges because they are safe, and there’s no need to invest in reviewing all the associated patents nor risk their business because someone missed a patent;

- recognize the right to repair also allows for lucrative service business with their customers, and don’t let over-zealous OEM service representatives scare them away;

- belong to their industry’s trade association that monitors the overzealous behavior of OEMs and their agents, and acts to protect them. Join today at www.i-itc.org.

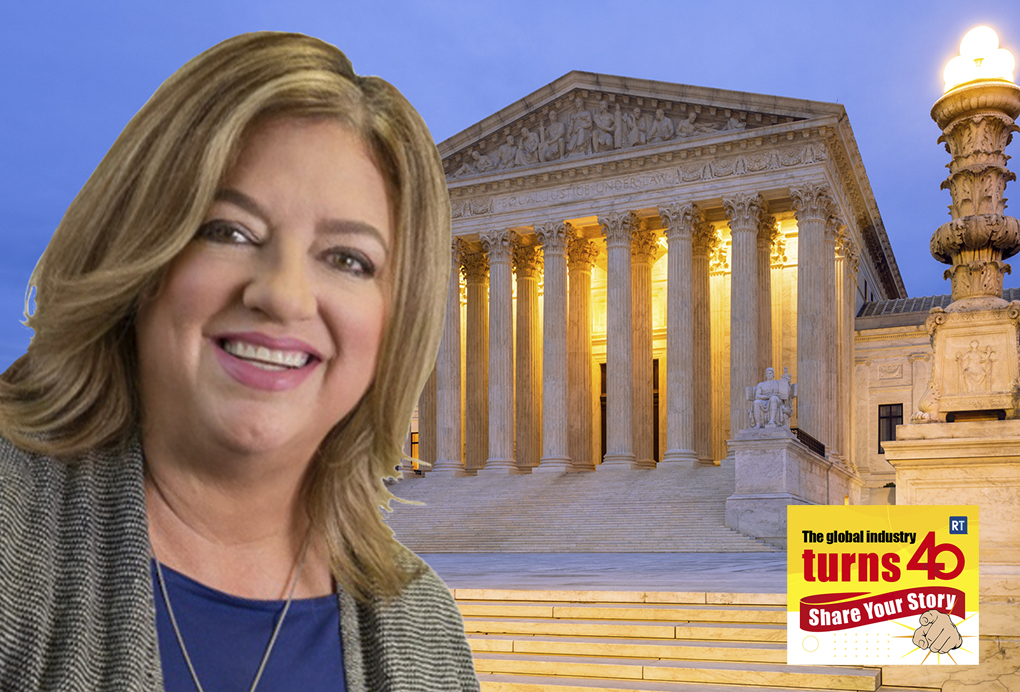

Tricia Judge has served as the executive director of the International Imaging Technology Council—a not-for-profit trade association serving imaging supplies remanufacturers and dealers—for 17 years. She was the executive editor of Recharger magazine for five years and a lawyer for 30 years. Judge’s work has been published in Recharger, Imaging Spectrum and several other industry magazines. She has won critical acclaim for her writing and industry advocacy. She prides herself in having assisted with the preparation of six friend-of-the-court (amicus) briefs and has presented the position of the industry to the US International Trade Commission. Since 2017, Judge has been the Senior Consulting Editor of RT Imaging World magazine and speaks at regional RT VIP Summits and RemaxWorld Expo in China.

Tricia Judge has served as the executive director of the International Imaging Technology Council—a not-for-profit trade association serving imaging supplies remanufacturers and dealers—for 17 years. She was the executive editor of Recharger magazine for five years and a lawyer for 30 years. Judge’s work has been published in Recharger, Imaging Spectrum and several other industry magazines. She has won critical acclaim for her writing and industry advocacy. She prides herself in having assisted with the preparation of six friend-of-the-court (amicus) briefs and has presented the position of the industry to the US International Trade Commission. Since 2017, Judge has been the Senior Consulting Editor of RT Imaging World magazine and speaks at regional RT VIP Summits and RemaxWorld Expo in China.

Her feature articles:

- Intelligent Office Solutions: cartridges workflow and more

- Static Control Continues to Set High Industry Standards

- Brewer Reveals Impact on Imaging Supplies by COVID-19

- Aftermarket Scores Another Win – Canon loses: zero degrees is not an angle

- How Trade Associations Help Protect the Environment

- The U.S. Department of Energy Scores High with Remanufactured Cartridges

- Clover Imaging Ready to Take Remanufactured to the Next Level

- Uninet’s Mike Josiah Awarded Diamond Pioneering Award

Her Judge’s Ruling opinion blogs:

- The Aftermarket Right That Shouldn’t Be An Afterthought

- Supreme Court Leans Towards Aftermarket

- Pivotal Patent Case has Support on Both Sides

- Council Presents its Issues to the US Supreme Court

- The Trump Presidency: Good or Bad for the Aftermarket

- US Supreme Court to Hear Lexmark Impression Products Case

- Election and Business Results Are In

- Canon’s Latest Dongle Gear Actions: Canon’s Checkmate

- Mobile Apps that Rule for This Judge

Comments:

You can add your ideas and thoughts on this article, “The Aftermarket Right That Shouldn’t Be An Afterthought” below or directly with Tricia Judge by email.

Leave a Comment

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!