Will Epson and Calidad Go Back to Court in Australia?

Will Epson and Calidad Go Back to Court in Australia?

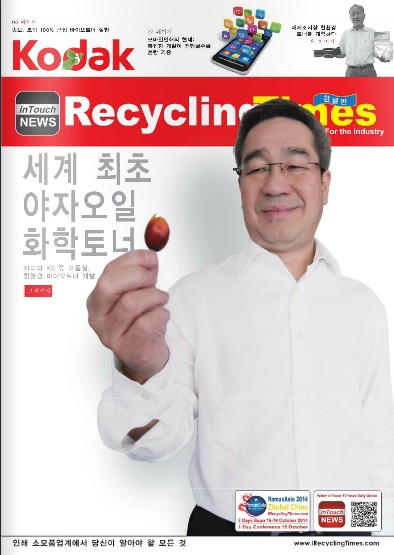

Dr Mark A Summerfield (pictured) shares his views with RT Media’s readers about the results of the recent decision in the Epson vs Calidad lawsuit handed down by Justice Burley. He asks:

When Does Importation of Refurbished and Refilled Printer Ink Cartridges Infringe a Patent?

Intellectual property rights continue to play a role in the ongoing struggle between printer OEMs and generic suppliers. For example, functional features of print cartridge technology can be protected by patents, potentially enabling the sale of copies to be restrained through court actions for patent infringement.

However, refurbishing and refilling of cartridges represent a grey area for IP laws. The default legal position is that once a product (which the common law would class as a ‘chattel’) has been sold, the purchaser becomes the owner, and is free to deal with it as he or she wishes, including reselling, donating, or disposing of it, whereby any subsequent owner may enjoy the same rights of possession. This raises the question of whether there can be an infringement of an IP right, such as a patent, when instead of making and selling a copycat product, a competitor legally acquires spent ink cartridges and restores them to (roughly) their original condition for resale? The answer – as I am sure any lawyer will tell you – is ‘it depends’.

A recent decision by Justice Burley in the Federal Court of Australia addresses a particularly interesting variation on this theme. Seiko Epson Corporation v Calidad Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1403 concerns the collection, refurbishment, and refilling of ink cartridges for Epson-branded printers outside Australian jurisdiction, and subsequent importation and sale of the refilled cartridges by Calidad within Australia. While the case covers a range of issues, including trademark infringement, trade practices and contract law, the most substantial aspect of the decision is whether or not importing and selling the refurbished cartridges constitutes an infringement of Seiko’s Australian patents covering certain features of its cartridges.

The short answer, according to Justice Burley, is ‘it depends’! In particular, it depends upon exactly what is done in the course of refurbishment, and whether this results in the product being ‘materially altered’, insofar as it is ‘an embodiment of the invention as claimed.’

A Purchaser’s Rights in a Patented Product

Under earlier Australian legislation, a patent gave the patentee an exclusive right to ‘make, use, exercise and vend the invention’. The current Australian Patents Act 1990 grants a more comprehensive right to ‘exploit’ the invention which, in the case of a product, includes to ‘make, hire, sell or otherwise dispose of the product, offer to make, sell, hire or otherwise dispose of it, use or import it, or keep it for the purpose of doing any of those things’.

Notably, these rights are in conflict with the common law notion of ownership of a chattel. Two competing legal theories have arisen to address this apparent problem:

- the doctrine of ‘exhaustion of rights’, where all patent rights of the invention are exhausted upon a first authorised sale of the patented product; and

- the notion that there exists an implied licence to use a product in any manner upon purchase unless the patentee imposes conditions at the time of sale.

The exhaustion of rights approach has been adopted in the United States, as was recently confirmed by the Supreme Court in Impression Products, Inc. v Lexmark International, Inc.

The position in Australia is, arguably, less clear. The most influential authority remains a 1911 decision of the Privy Council, in National Phonograph Co of Australia Ltd v Menck [1911] UKPCHCA 1; (1911), which was decided under the Patents Act 1903, and which – as Justice Burley most eloquently explains in Seiko Epson – essentially adopts the implied licence approach.

Justice Burley’s reasoning in Seiko Epson proceeds on the basis that National Phonograph continues to apply, and that the rights of subsequent owners of products embodying patented inventions are protected by an implied licence.

Scope of the Implied Licence

National Phonograph establishes that a patentee may impose conditions on the initial sale of products embodying a patented invention, thereby limiting the scope of the implied licence. However, such restrictions do not ‘travel with the goods’ – any subsequent owner receives the full benefit of the implied licence unless that owner has actual knowledge of the restrictive conditions at the time of acquiring the goods.

Justice Burley found that neither Ninestar (the company that performed the actual refurbishment and refilling of cartridges) nor Calidad (which imported the resulting cartridges for sale in Australia) acquired the products subject to any restrictions imposed by Seiko.

Importantly, his Honour found that ‘there is no difficulty implying the licence where the patented goods are first sold outside of the patent area (that is, broadly, outside Australia)’.

Rights to Refurbish or Refill?

Rights to Refurbish or Refill?

The ‘traditional’ position regarding the repair of patented products is legally simple: an owner has a right to maintain and repair a product that they own. However, at some point, a repair or refurbishment may become so extensive that the owner is effectively making a replacement product, which is, of course, an exclusive right of the patentee not encompassed by the implied licence.

Either way, whether an owner’s actions amount to a permissible ‘repair’, or an unauthorised ‘making’, is a matter of degree.

The difficulty for Seiko Epson is that regardless of whether refurbishing and refilling printer cartridges amounts to a ‘repair’ or ‘making’ of the patented products, the acts were not performed in Australia. Rather, the already refurbished products are imported and sold in Australia. Their importation and sale infringe Seiko’s patents unless covered by an implied licence.

The question is therefore not whether the refurbishment is an infringement of the patents, but rather whether modifications performed on the cartridges in the course of refurbishment and refilling extinguish the implied licence that undoubtedly attached to the original sales. As Justice Burley explained:

“The proper question is accordingly not based on a repair or making analysis, but rather whether the implied licence can be said to apply in circumstances where one owner of the product, Ninestar, has modified it and then passed title in it to [Calidad]. The relevant question then becomes; at what point has an owner of the embodiment made changes to it such that the implied licence arising from a sale sub modo is extinguished? No authority appears to have directly addressed this topic.”

‘Material Alteration’ – A New Concept in Australian Patent Law?

According to Justice Burley, the question to be addressed is ‘whether the product, insofar as it is an embodiment of the invention as claimed, was materially altered, such that the implied licence can no longer sensibly be said to apply’.

In simple terms, a modification that is unrelated to the patent rights such as, for example, painting the product a different colour (assuming colour forms no aspect of what is claimed), would not amount to a material alteration, and would not extinguish the implied licence. However, removing and/or replacing a component of the product that is actually an element of the invention as claimed may be a material alteration that would extinguish the implied licence.

The Claimed Invention

The invention protected by Seiko’s patents is a printer cartridge that includes a low-voltage memory chip, a high-voltage sensor device, and electrical contacts arranged in a particular way to reduce the risk of damage to the cartridge and/or printer as a result of short-circuiting between low and high voltage terminals.

A number of different products sold in Australia by Calidad were said by Seiko to have infringed its patents. Some of these products were refurbished using a process that involved resetting the memory chips electronically, without physically modifying or replacing any parts making up Seiko’s patented invention. Others, however, used a process in which circuit boards were temporarily removed from the cartridges, and the memory chips replaced with compatible devices.

For products having memory chips that were electronically reset without replacement or other physical modification of the cartridges, the court found that there was no ‘material alteration’. In particular, the information content of the chip, which is changed by this modification, forms no part of what is claimed as the invention. Thus, resetting the content of the chips does not result in the implied licence being extinguished, and importing and selling this category of refurbished and refilled cartridges does not infringe Seiko’s patents.

For the other categories of products, however, the court found that the modifications did involve a ‘material alteration’ such that the implied licence was extinguished. Replacing the memory chip – which is an explicit feature of Seiko’s claimed invention – was a material change to the embodiment of the invention as originally sold by Seiko.

Therefore, the outcome was mixed for the parties on both sides. While a number of categories of refurbished and refilled products, sold prior to April 2016, were found to lack the benefit of the implied licence, and therefore to infringe the Seiko patents, other categories of products sold since that date were found to be non-infringing by virtue of the continuing existence of the implied licence.

Conclusion – Innovative Reasoning, Ripe for Appeal?

There are innovative elements to Justice Burley’s reasoning, in view of which – along with the fact that the parties on both sides have some reason to be dissatisfied with the outcome – there is some possibility that the decision will be appealed. If so, it would be an opportunity for a Full Bench of the Federal Court (and possibly, ultimately, the High Court) to settle whether ‘implied licence’ or ‘exhaustion of rights’ is the correct approach in Australia, and to confirm or correct the reasoning developed by Justice Burley in this judgment.

So the question remains, will Epson and Calidad go back to court, and could it go as far as the High Court of Australia?

Related:

Comment:

How does this story, “Will Epson and Calidad Go Back to Court in Australia?” impact upon you? Please add your comments below.

Leave a Comment

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!